Welcome to Medterra’s “Live Harder'' series: Stories that empower our community – from elite athletes to regular folks – to pursue their dreams and live pain free. LIKE A BIRD After the leg- and lung-busting climb to the top of Mount Tom in California’s Eastern Sierras, the work is only half-done; the bone-rattling trek back down from the summit remains. Which is why, for Matt Segal and a small cadre of daring climbers, the preferred descent route is one few can even imagine — the aerial one. Hike and Fly they call it, and it is just as graceful and as simple as it sounds. Armed with ultra-lightweight paraglider wings that pack down to the size of a large water bottle, practitioners go by foot into the mountains in search of a suitable takeoff site and favorable weather conditions. Once at a launch site, they carefully fold out their paper-like wings and untangle the dental floss-thin lines, before finally clipping into their harnesses and preparing for flight. Like a child’s kite, a slight puff of wind or a brief sprint downhill is all it takes to set the wing into flight above them — and they’re off! Free to soar with the birds and return home to the valley below in the most elegant, effortless manner imaginable. Or at least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. Standing at an elevation of 13,652’, Mt. Tom dominates the skyline above the desert outpost of Bishop, CA in the Owens River Valley It makes for a coveted, dramatic and dangerous benchmark for Hike and Fly aficionados. “I don't remember a time when I questioned if I was going to make it out alive, to be honest. But I do remember one thing — a moment of pure, overwhelming panic when I thought I had been left alone up there,” recounted Segal. The flight off of Mt. Tom had gone terribly wrong; the dream of flying like a bird had turned into a nightmare. Segal’s broken body lay awkwardly on a steep slope of boulders and talus below the summit. He was alive, but with severe injuries and no guarantee of rescue.

BACKSTORY “I'm from Miami, Florida,” Segal says, “and started climbing at camp in North Carolina when I was nine. A few years later I found a climbing gym in Miami and that was it. — I just fell in love with it.” But he didn’t only fall in love with it: He was obsessed, training and preparing meticulously in a quest to become the best climber he could be. Soon he was winning national competitions and placing on the elite World Cup climbing scene. He moved to Colorado, doubled down on his training, and was in short order one of the strongest rock climbers in the world. Competitive burnout during his university years didn’t diminish Segal’s thirst for the pure act of climbing, so while he withdrew from the events that characterized his younger years, he continued to excel in the rarified arena of first ascents and incredibly difficult traditional rock climbs. Endorsements and expeditions followed, and he continued to push the limits of what was thought possible in the vertical rock realm. At this level, rock climbing is extremely focused and intensive, with top athletes training for months and years to complete a single route or series of moves on famed “test piece” climbs, or in the quest establish routes of their own. To balance this, Segal’s active mind kept him searching for complimentary ways to find excitement and challenge in the mountains, and he immersed himself in pursuits like skiing, biking and, fatefully, paragliding. “Paragliding just seemed like a really fun thing to add to climbing these big mountains,” explained Segal. “And not by the most difficult routes, like in rock climbing, but often by the easiest ones.” He already had lofty ambitions for his newfound passion: a hike and fly expedition to the Himalayas was on the books, with the goal of reaching and potentially flying from the dizzying height of 8,000 meters. In hindsight, Segal wondered if this frenzy of preparation was where things started to go wrong. “Preparing for the expedition I was doing a lot of cardio training. I was climbing less than normal but still frequently, and was paragliding as much as I could,” he continued, “so I feel like I was really stretching myself way too thin trying to do so many activities at once.”

A GUST OF WIND It was July 16, 2017. Segal and his group had summited Mt. Tom and readied their gear for flight. Four of the group took off successfully, leaving only Segal and his friend Cruise McLean. Segal would launch next, with McLean following shortly behind. Segal was strapped in and ready to launch, but before he could take off, a powerful gust of wind unexpectedly filled his wing and launched him skyward, immediately and violently slamming him back to earth. The life-threatening severity of his injuries were immediately apparent, and McLean leapt into action, stabilizing Segal as best he could and contacting rescue services. McLean sat with and cared for Segal for around two hours before the first helicopter arrived. This heli was able to drop a medic and supplies but was unable to extricate Segal due to the wind and terrain. Another six hours passed before the U.S. Army Chinook helicopter arrived and was finally able to hoist him out. After a brief stop at the hospital in Bishop, he was flown to Reno for intensive trauma care. In the end Segal severely broke both arms, sustained hairline fractures to his ribs, spine and pelvis, deeply bruised a knee and lacerated his calf. “I've already been fortunate to spend a long life in the mountains, and I've been lucky to walk away from a lot of close calls, but unfortunately my luck ran out,” explained Segal, in his first public post following the accident.

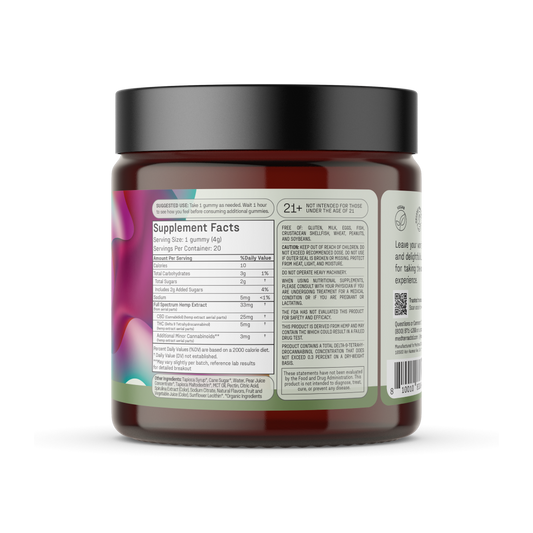

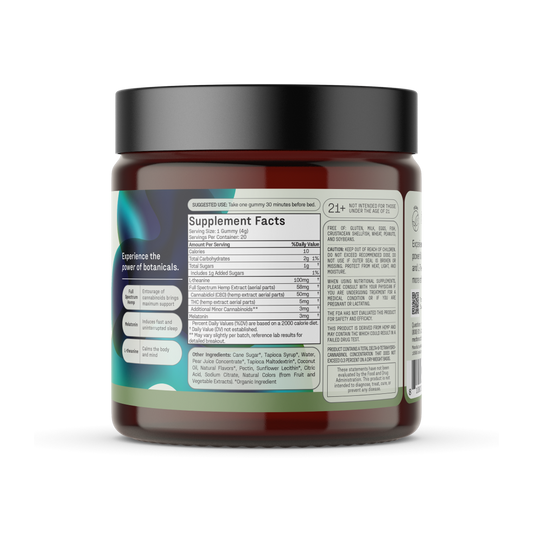

RECOVERY No loss of motor function. No need for a wheelchair. Ten weeks, and you’ll be good. That was the doctors’ miraculous prognosis for Segal’s recovery. Though he would need surgery on both arms, the other fractures were minor and would heal on their own. Despite the brush with death on the summit of Mt. Tom, it looked like recovery would be rapid and complete. “I couldn’t walk without help for the first three weeks,” recalled Segal, “and for that whole first month it was mostly just chiropractor visits and eating super healthy.” “That period is where I first started using CBD,” Segal shared. “Medterra’s Pain Cream in particular was indispensable while recovering from my injuries. I’ve been using their CBD ever since.” At the ten-week mark it was time for another round of X-rays, and the news couldn’t have been better: the fractures had all healed; he was cleared to take off the neck brace. And shortly afterwards he was reunited with his first love —he went rock climbing. He began slowly and carefully at first, but by month three he was back to climbing routes rated 5.13 (on a difficulty scale of 0 - 15, roughly). Today, Segal continues to climb professionally, and his thirst for adventure remains strong. He is currently working on establishing a new route on a 2,000’-tall wall deep in the wilderness of Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains. But what about paragliding? Would he go back? His body had recovered amazingly well, but what about his mind? “I didn't go back to flying. I realized that I fell in love with the idea of doing certain things, but not what it's going to take to achieve that idea. I never felt that drive for paragliding like I do for rock climbing.” Segal continued, “I learned that narrowing your focus can be really a positive thing. And two years after the accident I got back to climbing 5.14 again, basically the gold standard for professional rock climbers.” “Recovery is a slow process, and the only thing that I can say is be patient with yourself. Narrow your focus and don't spread yourself too thin. Sometimes you want to do as much as you can, and pack everything into this one life that you have. And for some people, that works great. But for me personally, I’ve realized I prefer quality over quantity.”